October 13 to November 3, 20252025 Residency:

Bel Falleiros & Renata Cruz

Bel Falleiros

BEL FALLEIROS is a Brazilian artist whose practice focuses on place and belonging. Starting with her hometown, São Paulo, she’s worked to understand how contemporary constructed landscapes (mis)represent the diverse layers of presence that constitute a place and how that affects those who inhabit them.

In her work, she creates spaces to be in community with nature, with our own inner being and with the beings around us. She is a fellow artist from Sacatar Institute in Bahia, Brazil (2014), Pecos National Park, New Mexico (2016), Burnside Farm, Detroit (2017), Santa Fe Art Institute Equal Justice Residency (2018), Socrates Sculpture Park (2020), More Art (2021), and Dia:Beacon artist-in-residence for the Dia Teens Program (2021-2) and Wave Hill (2023). She had a commissioned piece for the 37o Panorama of Brazilian art show at MAM, São Paulo (2022) and recently had a solo show, with a collection of works made in the past 7 years, at KinoSaito Art Center (2024).

In addition to her studio practice, she participates in collaborative projects across the Americas connecting art, education and autonomous thinking.

Falleiros lives and works between Stony Point, New York and São Paulo, Brazil.

Renata Cruz

RENATA CRUZ lives and works in São Paulo, Brazil.

In her work she seeks to create open and non-linear narratives, where diverse visions, voices and other manifestations of life are present. She appropriates clippings from literary texts, listens to personal stories and organizes them with collected images and other fragments of the world. Graduated in Visual Communication, UNESP, Bauru, Brazil; Artistic Education, UNAERP, Ribeirão Preto, Brazil, she was also a foreign student at the Faculty of Fine Arts of the Complutense University of Madrid, Spain and a postgraduate degree in Integrative Art at Anhembi Morumbi, São Paulo, Brazil. Among the exhibitions in which she participated are: 2021 Tomorrow is now - Labverde Festival; 2020, Amazona - Adelina Institute, São Paulo, Brazil; 2019, Reserve The abyss does not separate us, it surrounds us - Espaço Cultural Porto Seguro, São Paulo, Brazil; 2018, Forever and a day - MARP Ribeirão Preto Art Museum, Ribeirão Preto, Brazil; 2017, Forever and a day - Blanca Soto Gallery Madrid, Spain; 2016, Kaetemiru, time for changes - Aomori Contemporary Art Center Aomori, Japan; 2015, Liberation Área - Espacio Titilaka Lima, Peru. She currently teaches classes at the Tomie Ohtake Institute and Sesc Pompéia in São Paulo and is a teaching artist for the Escuelita en Casa project in the Queens neighborhood of New York.

Renata Cruz and Bel Falleiros:

to Place Truth in the Mouth of Art

In his Art of Poetry, Borges wrote: “They say that Ulysses, weary of wonders, wept with love at the sight of his Ithaca, green and humble. Art is that Ithaca of green eternity, not of wonders.” Brazilian artists Renata Cruz and Bel Falleiros' tandem residency — organized by The55Project in collaboration with Espacio 23 — was precisely an experience of “green eternity.” Synchronized, it was lived as shared movements, a dance of creative encounter open to others.

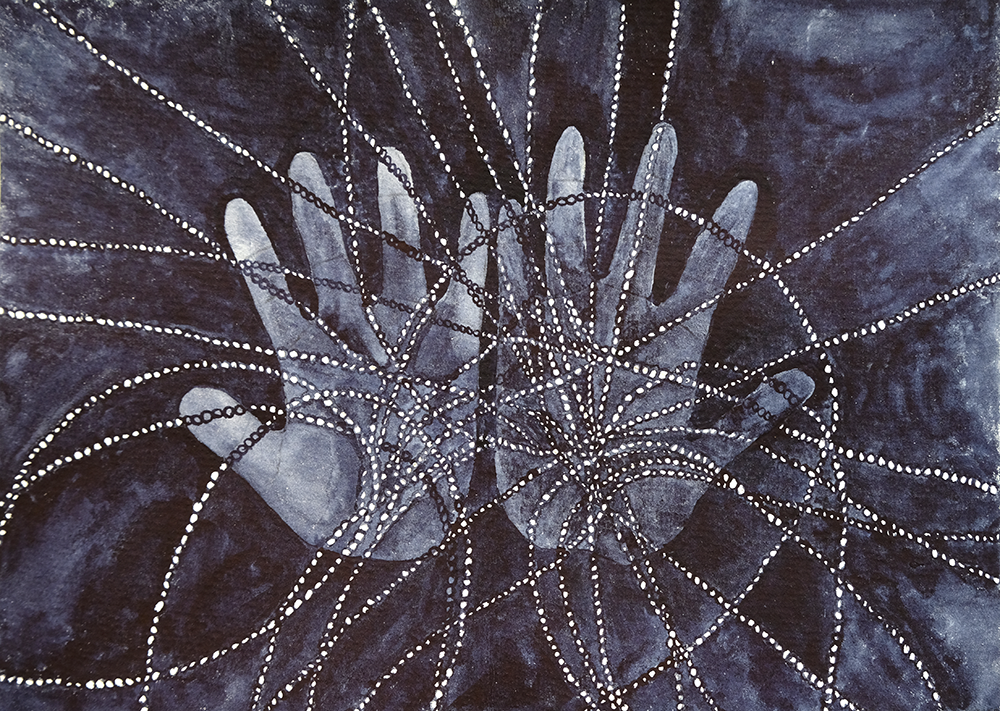

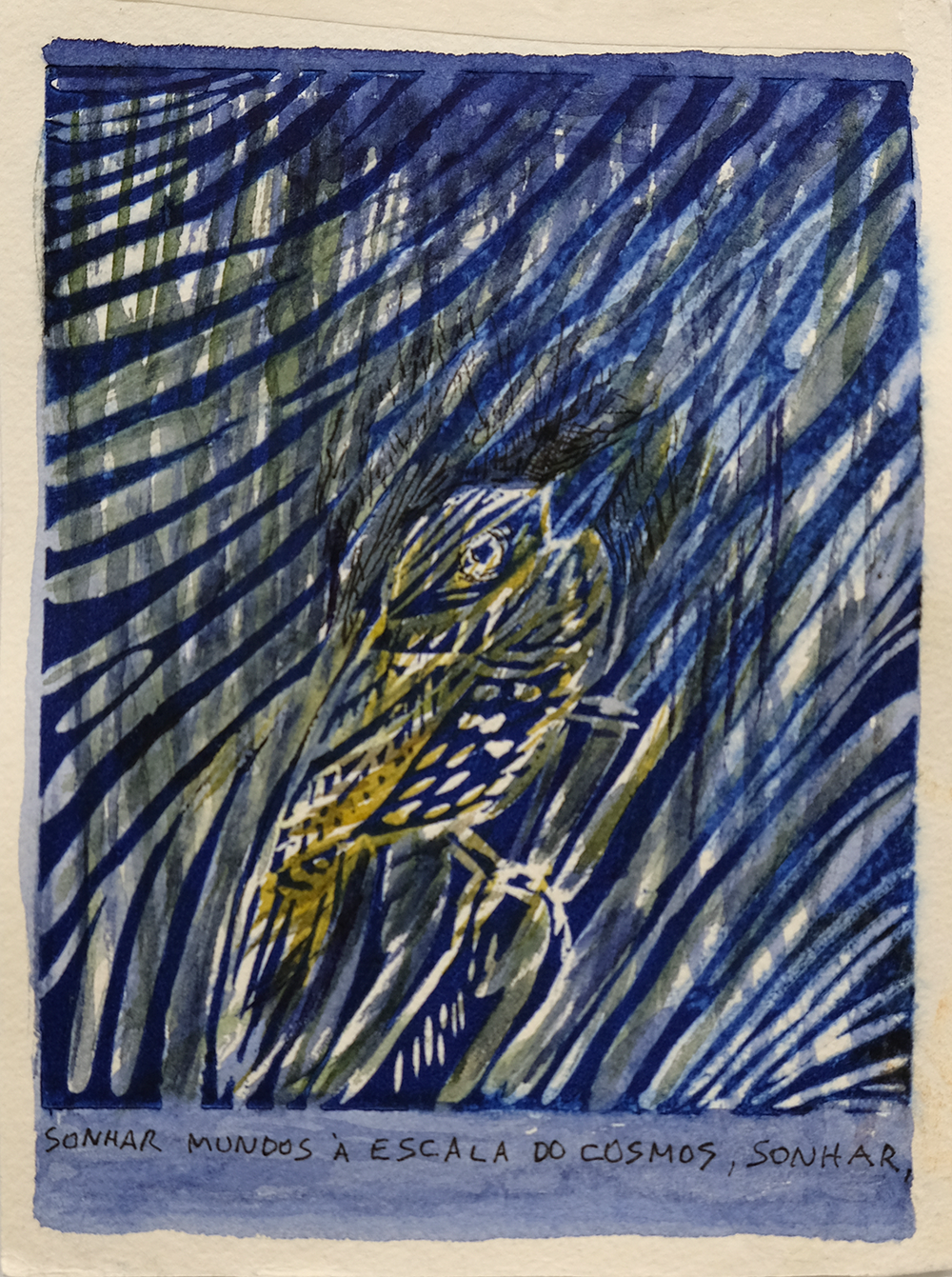

The work of both artists possesses the quality of leading us back to a vision of the essential through diverse means. Renata Cruz fills the world with her watercolor drawings and paper collages that portray beings of many species, binding them to one another, for she knows that all dimensions of life are connected. She also gathers stories of knowledge among people, often woven into books created by and for many. In her pedagogy of the Earth (a planet we have torn to pieces, yet which she insists on poetically rebuilding in her works) hands often hold leaves and stems, while living forms multiply in installations where birds, fish, skies, wings find a place. Those hands almost always duplicate the way her own paint and touch the other realms with infinite delicacy. The silhouettes of cut-out creatures, at times projected as shadows, or drawn on paper over found educational or explorer's books that contain something of herself trace a path of return to unity with the Earth.

The watercolor works that Bel Falleiros also painted for the residency by placing her daughter’s hands within the cosmos, radiated a mode of communion. Her oeuvre endlessly repeats the names of origin: water, earth, tree. And she recreates gestations in the womb of the cosmos through sculptures and land-art installations, as well as through paintings on canvas that gather not only forms but the very voices of plants and peoples. She travels through her ancestral territories and returns to sacred memory. From that learning she poetically reactivates the forgotten centers of origin within cities, seeking to heal the fissures between them and the natural environment upon which they were built.

But the residency was not only a setting where, together, they expanded previous learning from collective practices. While Renata lives in São Paulo and Bel resides in New York, they built the habit of meeting for extended times through online encounters where they still share their doubts and their discoveries. Sometimes they spend long stretches in silence while creating. There was a moment in Renata’s artistic “career” when she felt that living in pursuit of visibility and the demands of galleries was taking away her clarity. She chose to slow her life down, following the teachings of the Indigenous leader Carlos Papá, rooted in the oral transmission of knowledge and in the Guaraní worldview, which today illuminates the project of the two artists: “to step out of the noise in order to listen, to immerse oneself inward to awaken.” Thus she returned to others from her pure language, which is a slow process of drawing, and from her deep love for books that she unbinds, remakes, and intervenes in order to tell other stories, to “speak truthfully” of what she believes should be spoken about.

Both have coincided in feeling a call to the truth of being, understanding the urgency of building safe places to share vulnerability not only between themselves but with an ever-growing number of others, in virtual workshops or in those they have already carried out in person in various museums and art spaces in cities across the Americas. Each artist brought to Espacio 23 in Miami works that they had made independently, but there they also created pieces together with four hands, showcasing a significant capacity for convergence in their way of extending their senses toward the polyphony of the beings of each realm. They began dialogues with many visitors in which words resonated in the depths of each person with a deeply moving meaning. These encounters were conceived as binding ties that led us inside each participant, and, at the same time, outside of ourselves. We leaned out toward a threshold where the truth of each search illuminated visions that later flooded the residency space and gave rise to new works.

There is something important that should be said: their works, individual and joint, are logbooks of their vital journeys, in a certain way images, scenes, or physical spaces of encounter where traces remain of what has been seen, lived, and understood. But they are not aesthetic objects as an end in themselves. They are works open to their ultimate meaning, which is the potentiality of shared learning and the desire — high in its aspiration, deep in its heart — to create atmospheres for dreaming other common futures. And for this reason, at different moments, both have long since stepped aside from the rules and know-how of the art market, from the social codes that demand modes of insertion and ascent inscribed in the tables of success, yet devoid of soul. What they seek is Diogenes’ lamp, the nakedness of other truths. And a tenderness that, in Renata Cruz’s words, is inseparable from a “feeling of extended family” that advocates not only for the members of the human tribe but for small creatures such as the Amazonian warrior ants, whose prodigious march with its cortege of countless species she has painted. Or like the vermilion flycatcher that crosses the Americas from the southern United States to Chile, and whose silhouette she repeated on the pages of a book that tells the story of how its feathers were dyed red while saving a human brother. “The forest has more eyes than leaves,” Renata wrote in a series of drawings, repeating the phrase of the Brazilian Indigenous leader Ailton Krenak. In 2011, she made as many watercolors as a full rotation of the Earth around the sun (one for each day of the year), drawing objects exchanged with people in parks. She paints in her watercolors what she learns from other beings, something that includes people, plants, and all the creatures that move in water, air, or earth. In collaboration with Laura Gorski, she handcrafted an Encyclopedia of Local Knowledge and Medicinal Plants, gathering testimonies among communities in Oaxaca, Mexico, and among Indigenous and Black communities in Brazil, as well as on the streets of Avenida Paulista in São Paulo.

Renata and Bel understand art as a form of imaginative pedagogy of love; a word that cannot be named without being thought in relation to another, and that calls for co-existence. Love repeats the phrase Bel has inscribed in her clay installations or in her works on paper: “We are one single heart, we are one single Earth, we are one,” echoing the words of the Yanomami shaman Davi Kopenawa. Both have converged in this pedagogy, which they partly conceived after walking long stretches alone, as a refuge for artists eager for truth in their creation. They know from experience that to travel that uncertain path and to create far from the stages of spectacle, one needs the sum of others, and of conversations, confessions, and the legacy of those who long before dared to walk along trails often distant from easy or immediate recognition.

The project they brought with them to Espacio 23, Árvores do América, contains in notebooks written in Spanish, Portuguese, and English the stories of those who, as Agnes Martin wrote, “dared to seek their own path.” From the helplessness of the time when they and other close artists who were exhausted by soulless meetings stepped aside from what was advisable for advancing their careers and decided to walk with less clamor and greater meaning. They were sustained by the discovery of the experiences of women such as Mierle Laderman Ukeles, whose vision of “Maintenance Art” carried the notion of the care present in everyday tasks into the field of art. Or that of Carmen Herrera, who learned not to be intimidated by anything; and Cecilia Vicuña, who spun on the margins of the world the mythical spiderweb of her work. They also found inspiration in the story of one-of-a-kind creators like Felipe Ehrenberg, a neologist by his own definition, who always made art on a tightrope anticipating practices that radiated alternative meanings around him. They've sat in the shade of thinkers such as Parker J. Palmer, seeking to bring together, in a life inseparable from art, the ethics of a way of living in inner communion and in community with others. Like Ana Mendieta, the artists sought to restore bonds with the universe, and to attend, as Doris Salcedo does, to the need for suffering to be heard. In this way they extend the echo of other men and women, tree-beings, whose experiences they transcribe very simply onto living pages, creating guides of encounter with which they activate other possible ways of being in the world and of moving among all the kingdoms of the Earth. Each visitor to Espacio 23 received a copy of the publication in an atmosphere that invited them to walk through their inner space and to draw seeds of knowledge in a meaningful process of exchange entirely alien to the idea of relationships of convenience that usually dominate art spaces. In their workshops, they often ask about the people who have illuminated others in their way of moving through the world. And so, they keep gathering tools to survive in the open, in that space propitious for experimentation. They are “happy to serve as a path of growth,” but also feel the responsibility of being artist-watchers before our shared present.

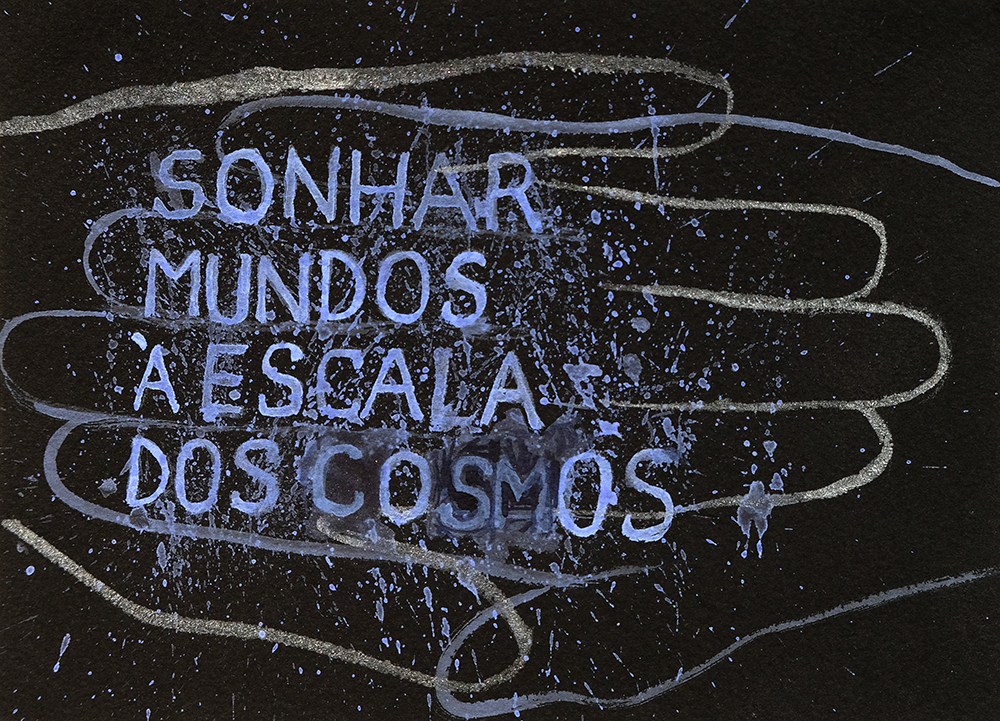

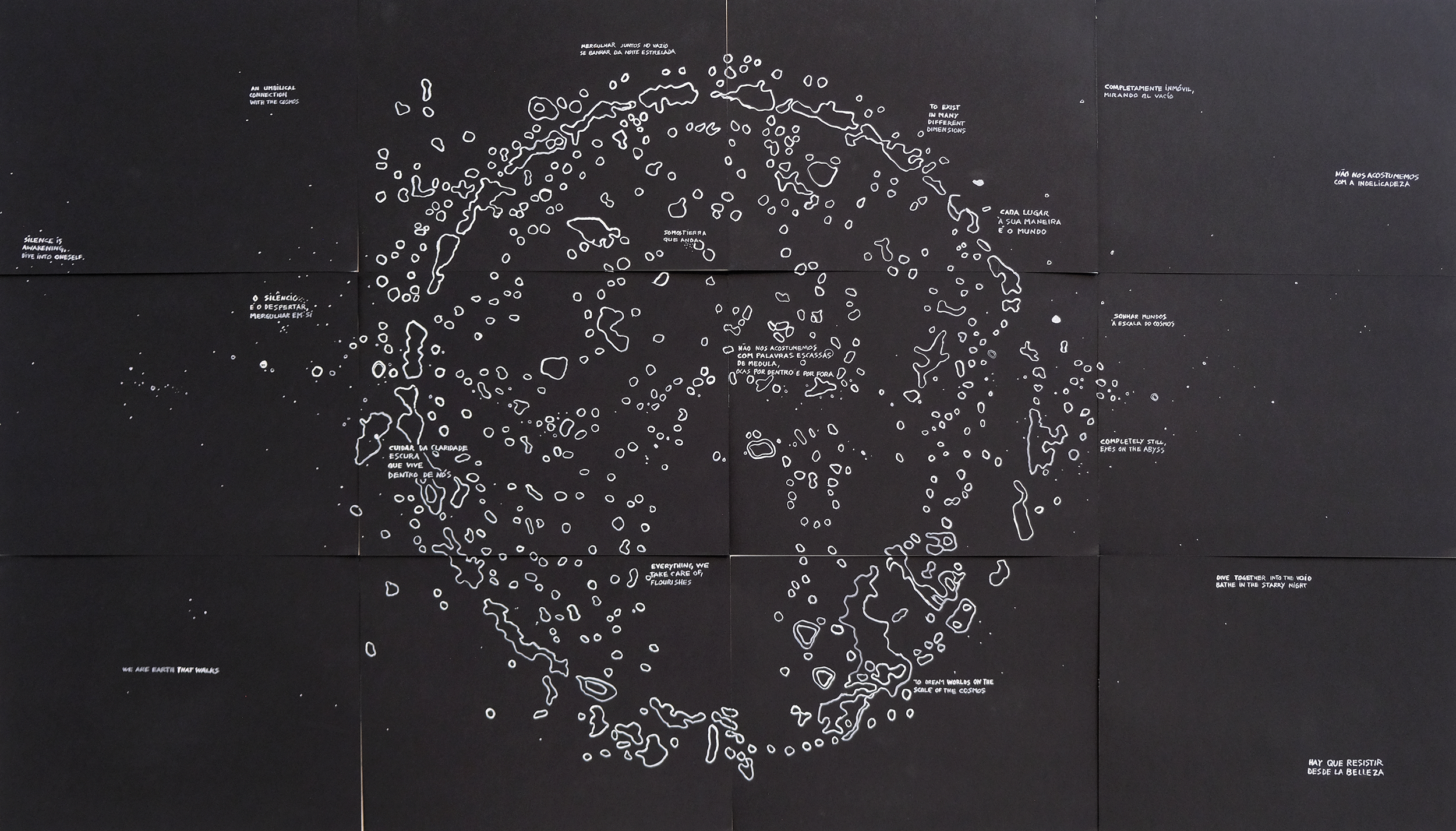

Although it was initially possible to distinguish each artist’s creation at Espacio 23, the resonances proved more revealing. “One must resist from beauty,” one of them wrote, echoing Cecilia Vicuña’s motto in one of the many thought-notes that each writes by hand and that they brought together in a single format for the final exhibition titled Inward Vastness. During the first visits, the spaces where each deployed their works were connected, yet it was possible to differentiate them. On the white surface of Renata’s watercolors, the bodies of plants, insects, amphibians, and birds appear painted in translucent rose, or in extended greens, yellows, and reds. They exist in a unique conjunction between drawing and painting that suspends them in time over fragments of a blue vastness filled with points of light that burn in silence and remind us that everything is made of stardust. In works with two or more folios, like the pages of her books unfolded, the forms of life pass from one side to the other. Another watercolor shows her taking a step: over her skin the red feathers of the scarlet ibis sway gently, and the potential movement suggests that, as she moves forward, the contour of an entire cosmos will change place.

She, they, know that the calcium in the bird’s bones, the iron that colors our blood red, or the carbon that feeds each leaf, come from stellar transformations. On the opposite wall, Bel, who had previously created immersive sound installations gathering the sound of many forms of life, painted on paper the hands of her daughter Cecilia. The lines of her palms extend or converge toward a space filled with a deep blue similar to the vast darkness of the infinitely expanding cosmos. Phrases by Cecilia Vicuña on small slips of paper and paintings marked the beacons of Bel’s journey: “an umbilical connection with the cosmos,” and “to go to the root of the mystery.” The two artists encountered these phrases during the residency. She also painted vessels as forms that connect us with gestations in the darkness of the womb-vessel and of the universe that ceaselessly brings forth myriads of life forms, like a small leaf swaying in the wind, whose movements simple yet marvelous.

In the final exhibition, the artists transferred both of their watercolors onto one wall, constructing a single space that asked us to read the planet differently and, above all, to imagine another way of assuming our interdependence. They painted four-handed drawings merging forms of life in predominant indigo blue, a color that unifies the continents because it was a sacred pigment in ancient America as well as in India. Their carpe diem is not only for humankind. It is a reminder of the vulnerability of every species that shares our present time, for each being — vegetal, animal, astral — is linked to all the others. Pouring the work of each artist into a single installation and creating a joint work amounts to knowing that authorship is a channel of expression, but that the message is more immense than the borders of each being and that it forms a powerful current that speaks with many mouths. What moves us, beyond the beauty of the life forms painted in indigo, is the truth they radiate, the force of a call all the more powerful because it lies beyond itself, and summons us to what Davi Kopenawa voices: “To make our ancestral animal souls dance.”

There were many phrases in the final installation heard from tree-beings of other places and times, as well as from Miami. They sparkle like stars in their simple and exact form of pasted paper slips, amid the watercolors of creatures and cosmos in which the artists have connected precise territories of Miami to the universe. An entire wall was dedicated to its place of origin: the Miami Circle, where the two painted their watercolors in blue and luminous whites invoking the knowledge gained during the residency and at other moments.

Bel set out on her drift through cities at a time when, according to her, she “didn’t know how to do anything,” yet her body connected with places. She ended up being led toward ancestral paths until she found the origin of urban spaces. It was the vanished zero point where she began to recover forgotten rituals, and the connection with the territory of the beginning suffocated in the vertigo of constructions. Her relationship with the layers of memory of places allowed her to understand that “we do not care for sites because we do not know how to create belonging.” Thus she has reclaimed hills and sacred mounds. The places fostered encounters with women of the Tewa people who taught her to think how to create what is necessary to open the way to the sacred, to healing, and led her to the ancestral language of clay, so close to the processes of creating networks of affection and creation. Her mounds embody the principle of anti-monumentality that erodes hierarchies: They are an art of the earth created to gather with others.

The Miami Circle that Bel Falleiros and Renata Cruz recreated in Inward Vastness, in a small-scale indigo watercolor, is an archaeological site of the city. Also known as the Brickell Point Site, it was possibly created two millennia ago when the Tequesta people built the center of their world in a perfect circle of 38 feet with post molds containing 24 holes or cavities carved into the limestone bedrock. This “omphalos” (from the Greek ὀμφαλός, “navel”), one of those sacred points that functions as the center of the world, was rediscovered at the end of the twentieth century. It was inscribed on the National Register of Historic Places before it was buried beneath layers of stone as a strategy of preservation. Both artists followed the trail of the people who have fought to keep that space alive, such as the community leader Catherine Hummingbird Ramírez, who for long periods went every seven days to activate the ancestral energy of the place, and the archaeologist Robert S. Carr, one of the site’s discoverers, who has dedicated part of his life to understanding its meaning. When Carr asked some of the various Indigenous groups who, having been displaced from the region long ago, came to visit it, why they traveled so far to be there, it was revealing to hear their answer: “We have come to listen to the Circle.” He thus learned that many Indigenous people believe that other groups will better hear the voice of their ancestral elders when a circle is discovered. And so, each time a millenary place is found, they make a pilgrimage to know whether it is the circle that has activated the awaited time. The words of these guardians were inscribed in the watercolor along with other phrases gathered in the time shared with other thinkers of the Americas who are guardians of the Earth.

In any case, the cyanotype on fabric that Renata Cruz and Bel Falleiros created together is an echo of that listening. The pair investigated the ancient mound-building cultures of Florida — in places like Deptford, Weeden Island, Belle Glade/Fort Center, Safety Harbor, Calusa, and Tequesta — for whom the landscape is incorporated into the sacred and living architecture of funerary centers connected to memory. They learned that the figures raised upon the territory reflect the constellations and the way that these cultures read in the vault of the sky what is written for the face of the Earth and its cardinal points. Thus, the serpent of Ortona Indian Mound Park is a symbol and reflection of a stellar constellation. With this knowledge, the artists traced the forms of their textile cyanotype, laid on the floor directly beneath their evocation of the Miami Circle.

Within the interior architecture of Espacio 23, they brought the legacy of those millenary constructions raised over generations, with the ancient notion of a way of inhabiting the territory by inscribing within it the bond between community and sky. In fact, the guiding phrase of this entire project is a Walt Whitman line in Leaves of Grass: “We all breathe the same air under the sky.” For this reason, this sky-earth reflection, this mirror between the places above and below, does not end with the watercolor and the textile cyanotype where they painted the constellations that gravitated at a precise time over Miami. Like each of their installations, it remains in the vision of the present of the city’s current inhabitants. It is an invitation to care for a territory in order to move forward from an ancient knowledge that they place in the hands of each person with the firm delicacy of their respective works.

The joint project of Renata Cruz and Bel Falleiros is an invocation of the hope Byung-Chul Han references when he writes about a movement of search “toward the unknown, toward the untraveled, toward the open, toward what is not yet.” And it is sustained by a vision attentive to the future, illuminating it with the courage of collective action: to place truth in the mouth of art.

Adriana Herrera, Independent Curator

Exhibition Artworks

About the workshop

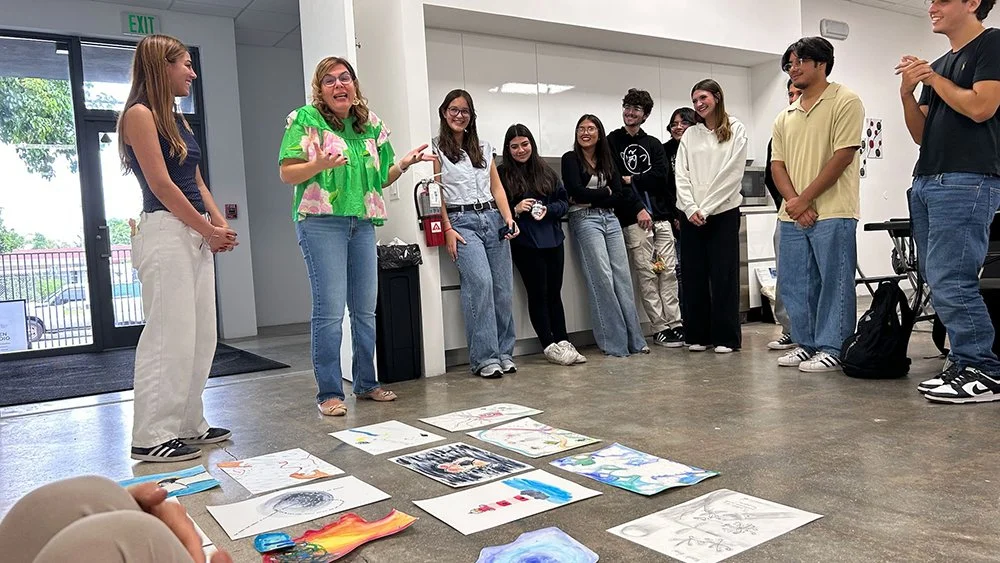

In 2025, artists Bel Falleiros and Renata Cruz took part in a residency at The55Project Art and Residency Program in Miami. During their time in residence, they developed a collaborative investigation into inner landscapes, perception, and expanded notions of territory.

The residency culminated in the exhibition Inward Vastness, which brought together works that explore intimacy, scale, and the subtle geographies of the inner self.